|

|

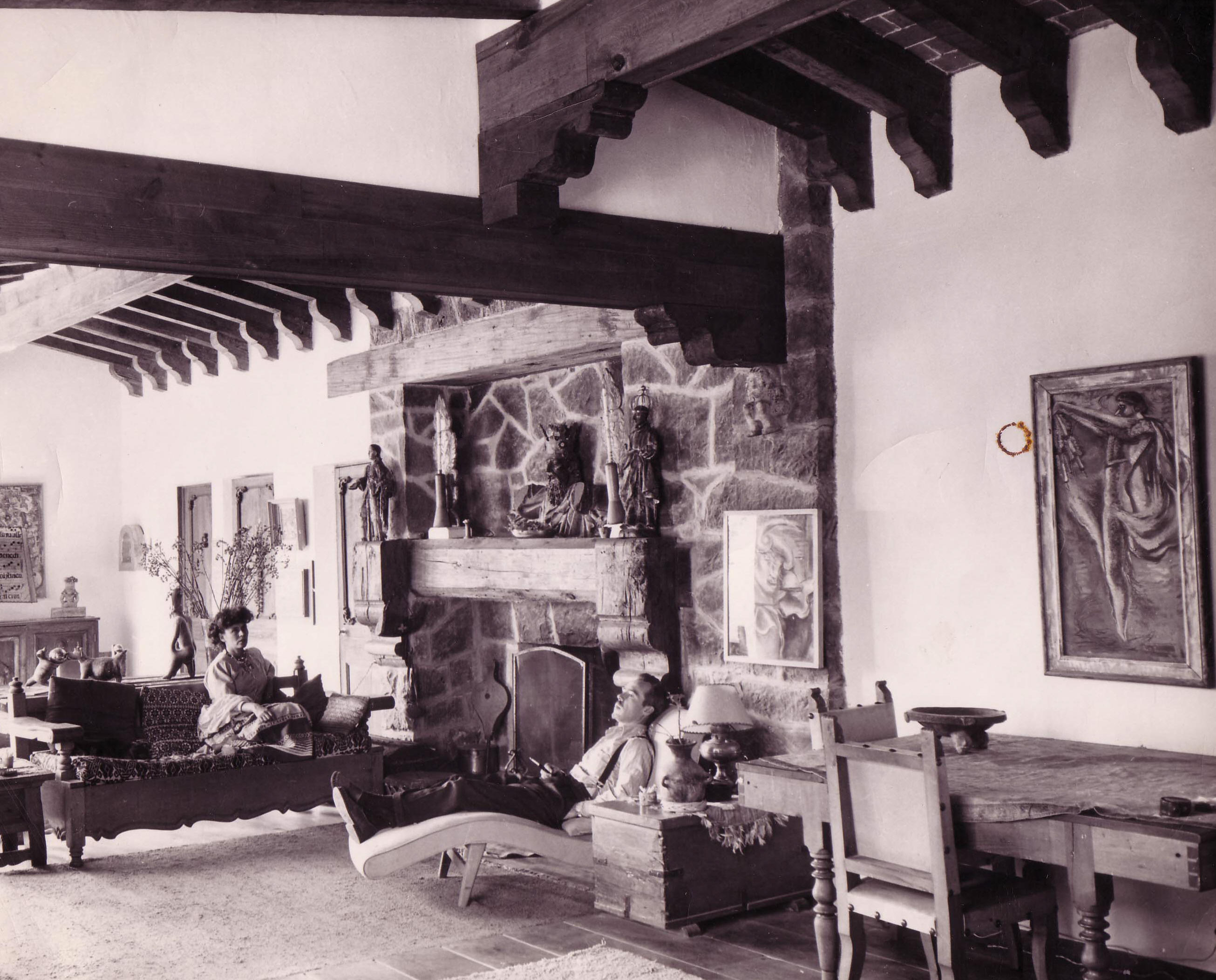

| Annette with her sons Luis (left) and

Charles |

Mexico

City, Jan 1, 2002

Dear Mr.

Hocker:

It was a

pleasure to hear from you. I apologize for not getting back to you sooner,

but I have been working

on this reply since you emailed me. I will try to answer your questions in

the order in which you give them, more or less.

I first remember meeting Conlon when we were

living in our house on Calzada de las Aguilas #50, probably around

1943/44. My father was away at war (he was stationed on an aircraft

carrier, the USS Bon Homme Richard, in the Pacific Ocean.) My mother,

Annette, my brother Charles and myself were living in the above-mentioned

house. (Aguilas #50 was built by my father and mother with Arquitecto

Manuel Parra on a large piece of land, about 7,500m2. On this

same property, in 1948, my mother built another home, Aguilas #48. This is

the house in which I now live.

|

| Annette and Conlon, Aguilas No. 48 |

Conlon built his sound proof studio in the rear of this property.

Later, when he and my mother divorced, he built a small house next to his

studio and this property became Guiles #46). My mother was a very

gregarious person and always had many friends visiting. As a five or six

year old boy, I never thought of Conlon as anything more than one of her

many friends. (Years later my brother and I learned that my parents'

marriage was really over before my father joined the war effort. They had

decided not to let us know this in the event that my father might lose his

life. This way, we would simply think that he died in action and never

know that he and my mother had had a marriage that was in serious trouble.)

In any case Conlon was a frequent visitor.

Before my

father left for the war, my parents were involved in and formed part of a

group of friends that included artists, dancers, people in the music and

theater world and bullfighters.

I

think you know that my mother was an artist. Though my father was by

profession a businessman, he loved the arts and preferred to be among what

was then thought of as the "bohemian" crowd, than the business

group. He and my mother knew and socialized with Diego Rivera and Freda

Kilo, Jose Clemente Orozco and his wife Margarita, Juan O'Gorman and

Helen, Wolfgang Paalen, Rufino and Olga Tamayo and many other artists. My

mother was also friendly with David Alfaro Siqueiros and his wife

Angelica. My father's portrait was painted by Diego Rivera in 1943, before

he left for the service. I own this painting, and it hangs in my house

today. Orozco painted my mother's portrait. She also had portraits painted

by Jesus Guerrero Galvan, Federico Cantu and, later, by Pedro Friedeberg.

When the well-known American Black singer, Marian Anderson, came to Mexico

to perform in Bellas Artes, she was a guest in our house. My father taught

her the words and notes to a popular Mexican song, "Las Golondrinas,"

that is traditionally sung as a farewell song. She sang this, in Spanish,

at her last performance and received a tear-filled, standing ovation.

There is a photograph that was taken in front of

the main door of our house, of my brother and myself as small boys

standing with our parents, and Orozco, Marian Anderson and the bullfighter

Silverio Perez.

I give you

this information not because it particularly pertains to Conlon but

because it will give you some background as to the social scene he came

into when he met my mother.

Some time

after my father left to serve in the U.S. Navy, I recall my mother going

out in the evenings.

This

certainly must have been the period of time that Conlon was visiting. She

would tell my brother and I that she was going to a concert, which, she

explained, was going to hear music being played. We had a "nana"

that would take care of us. But one of my early memories, which had an

irksome connotation for me, was that she was going out "to a

concert." This meant that she would not be with us in the evenings.

This, however,

did not color my feelings about Conlon.

For me Conlon was always a pleasure. He was a nice and

interesting person to be around, and as far as I can remember he was never

hostile toward my brother or me. Quite the contrary, he was usually amused

by what we said or did, would laugh easily, and was, in general, totally

permissive. If my mother thought it was time for us to go to bed and we

wanted to stay up, he would say," let them stay up." I liked

going to a shooting gallery in San Angel at 20 centavos for 9 shots. My

mother would only pay for one round. Conlon would pay for as many rounds

as I wanted. I loved sweets and ice cream, which my mother was against and

never seemed to have in the house. Conlon would allow this. On one

occasion, driving alone with him in his car, he actually stopped the car

at an ice cream store to buy me a Popsicle, called "kikoleta," a

favorite item at that time. I

was flabbergasted that he had done this for me!

My father

survived WW II. During

part of his time in the service my brother and I traveled with my mother

to see him in Navy boot camp in Gulfport, Mississippi, and in Newport,

Rhode Island. Later we travelled to Reno, Nevada, where we stayed in two

separate "dude ranches," (essentially divorce residences) for

six weeks. Charles and I had no idea why we were in Nevada, (the only

state in the U.S. that, at that time, allowed for uncontested divorces).

We were told about the divorce after the war, after it had become a fait

accompli. This news was given to us in our parents' bedroom in the Aguilas

#50 house right after my mother had nursed my father back from an almost

fatal bout of true tomane poisoning. […]

Needless to say their divorce was shocking for me. Though my brother was older and may

have sensed something, I had no idea whatsoever that my parents' marriage

was in trouble, and I was upset and confused by the break up.

After this my

father remarried, in 1945, to Helen Hall. He resumed his businesses in

Mexico and rented a house in San Angel, at General Aureliano Rivera #4. Here he lived with his new bride, a

young woman my brother and I liked immediately and have cared about for

years to come. My mother married Conlon about a year later. When my father

and Helen moved out of the Aureliano Rivera house to live in a new house

that my father had built on Calz. Taxqueña, my mother rented Aguilas #50,

and she and Conlon moved into this very same Aureliano Rivera residence.

This was the house that had walls that were about one meter thick. And

this is where I got to know Conlon much better as a person and as a

stepfather.

At Aureliano

Rivera Conlon was always working on some project, usually something to do

with music, or recordings. One

of the first projects I distinctly remember was a mechanism he had

acquired which looked like a turntable with an arm to play records. But in

this case the arm, with a diamond stylus, would not play a record but

would cut a record, that is, cut the grooves into a plastic record like

disc. As it would cut the recorded grooves a thin filament of material

would come peeling off the disc, like thread, and wind itself away into

twisted balls. We would find these black filaments all around the living

room. We could speak

into a microphone and have this mechanism record our voices.

|

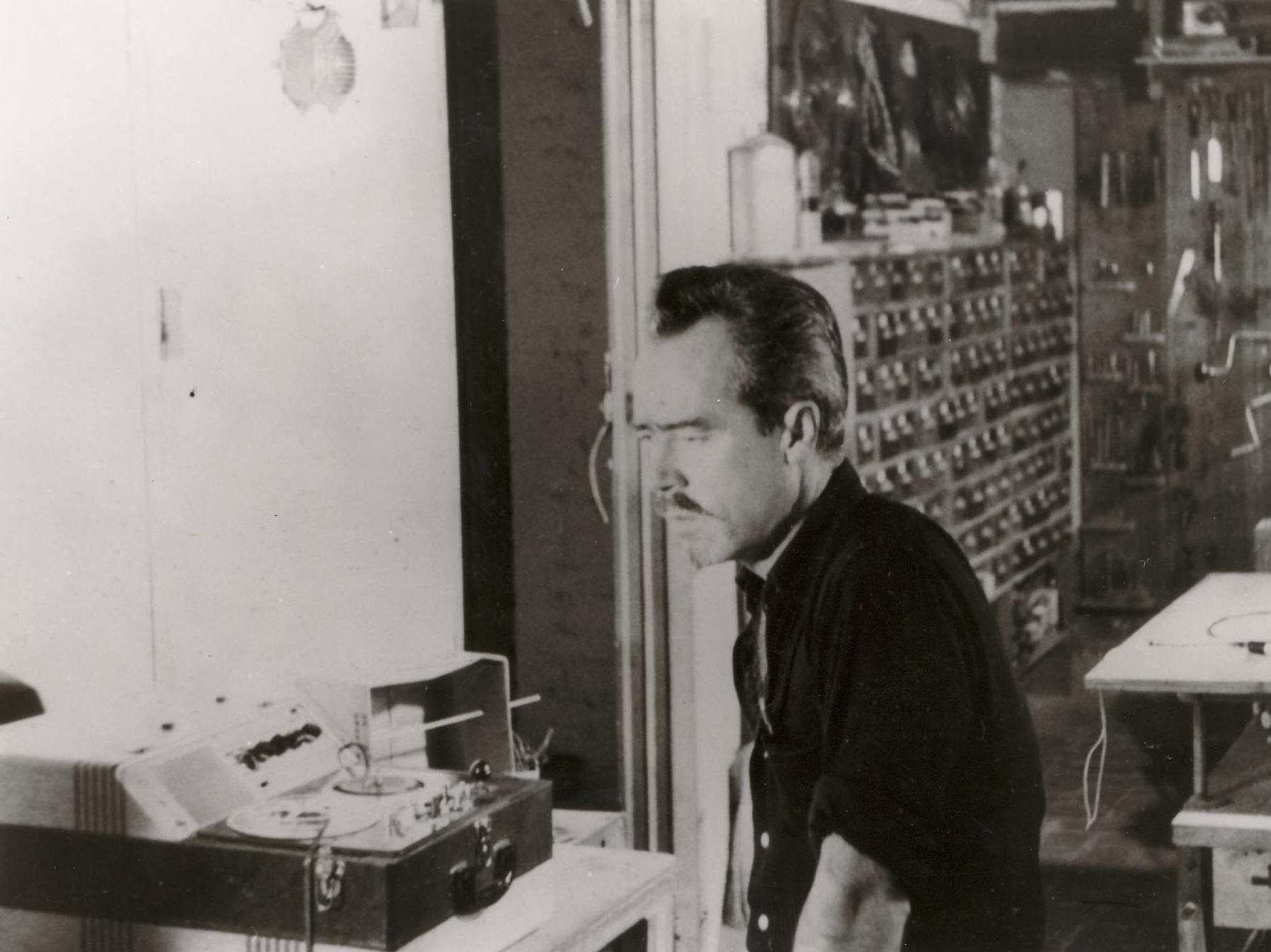

|

Nancarrow

experimenting with a tape recorder |

Another devise

that Conlon used, at a somewhat later date, was a tape recorder with large

reels and thin, light brown recording tape. As I remember one of his early experiments was to record

percussive sounds of a variety of drums or other instruments on to this

tape. He then would cut the tape into small sections, some as small as a

centimeter or so. Subsequently, he would tape these sections together with

some sort of scotch tape in a deliberate pattern that he hoped would form

his composition. He would then play the composite tape back to hear what

it would sound like. Eventually,

he had to abandon this procedure as it was not only terribly time

consuming but did not give him the precision he desired.

One of

Conlon's closest friends at the time was an American man named Bob Allen. Allen's wife Angeles was Mexican, and

my mother and Conlon and Bob and Angeles were frequently together. Bob was

a technician of some sort and was helping Conlon to develop an instrument/mechanism

that could use piano like hammers to strike any of a series of surfaces.

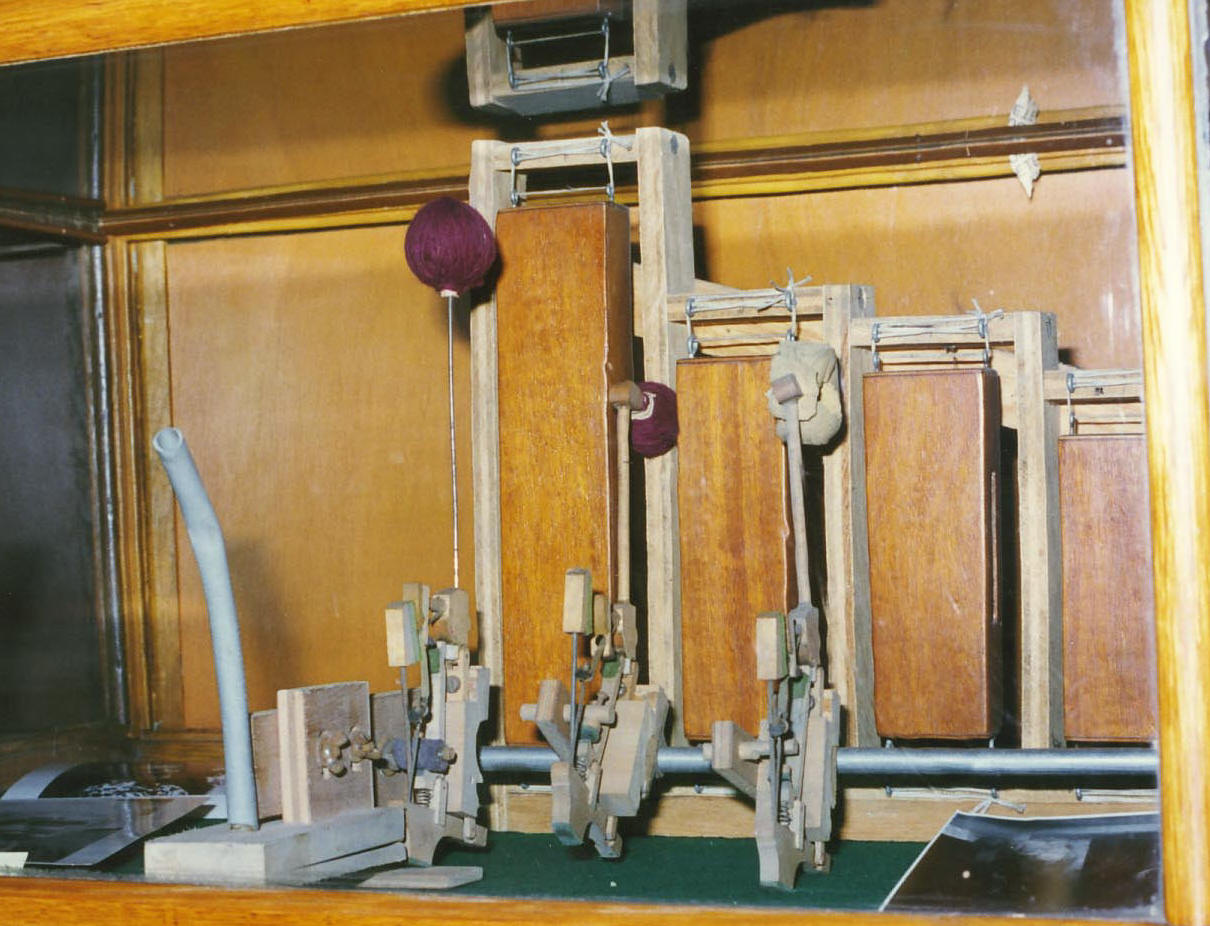

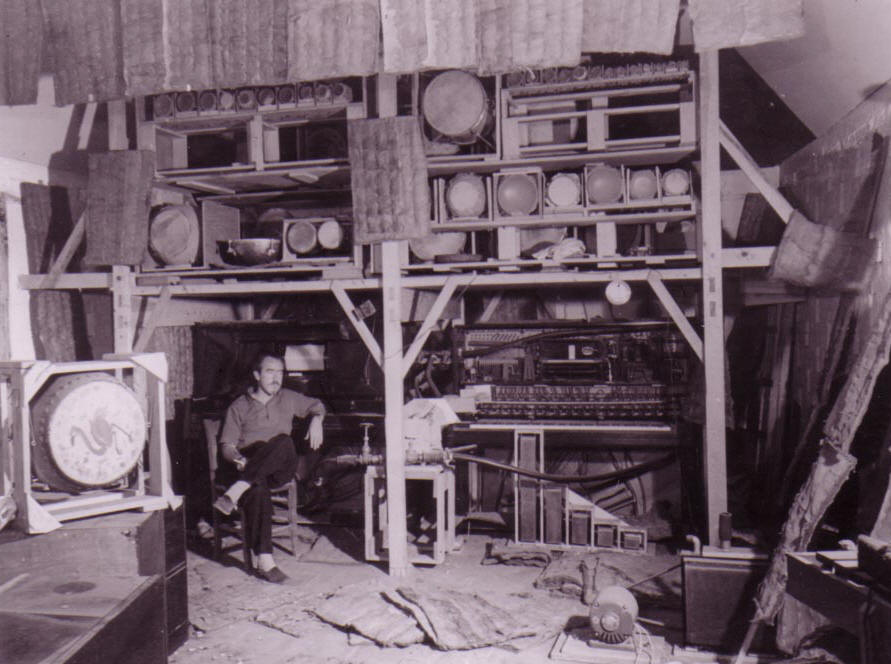

|

|

Piano hammers operating percussion devices. Fotos:

Jürgen Hocker |

I

believe they would rely on an air pressure or vacuum device to activate

the hammers, possibly via a perforated roll like the player piano. At

that time Conlon purchased quite a number of drums, some rather well made

and handsome ones which I think were Chinese, but also others that might

have been Indian as well as Cuban and Mexican. These were later put into a

large vertical wooden rack that went up about three to four meters and was

about six meters wide. Included in this rack were a number of drums that

Conlon himself made.

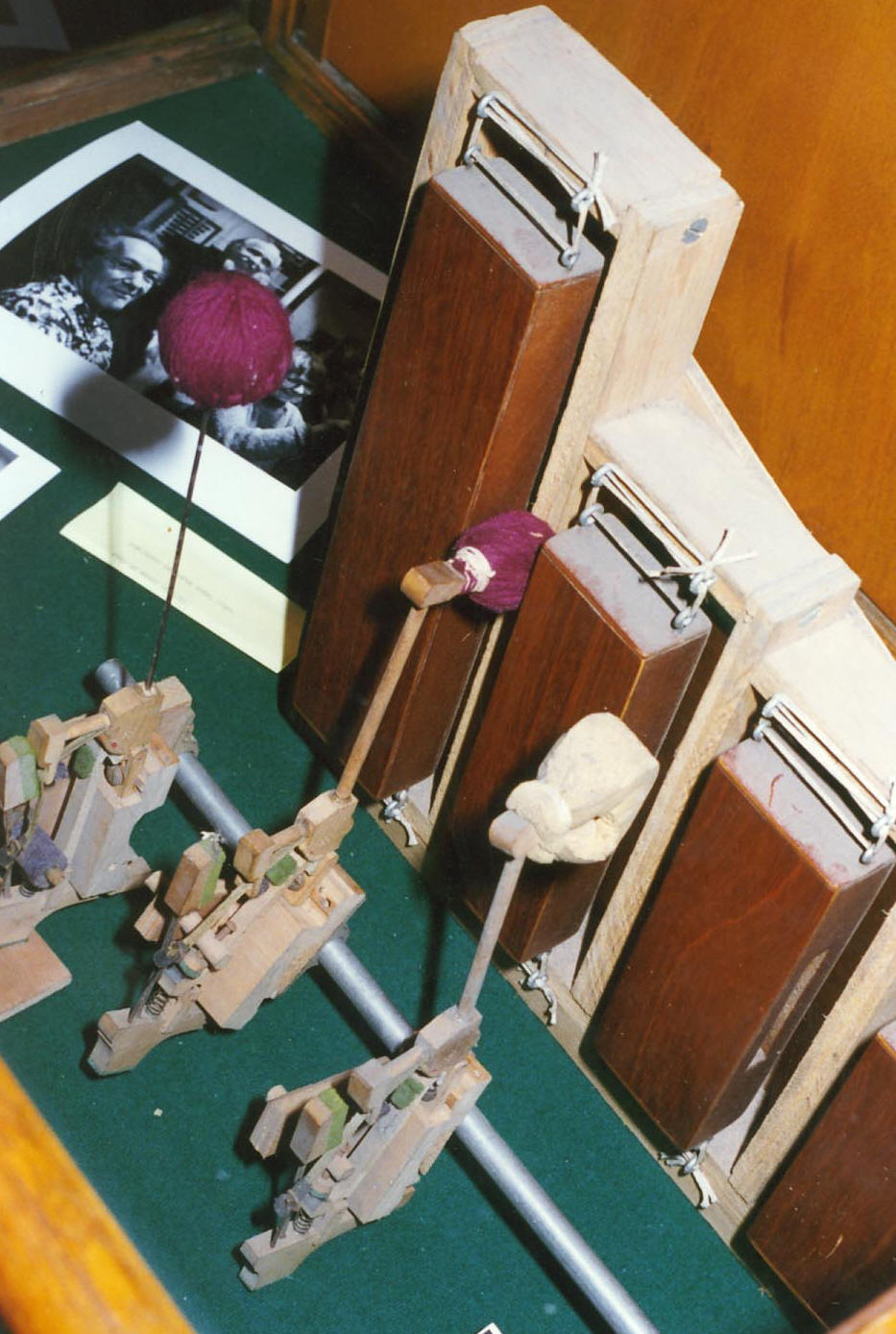

Nancarrow and his percussion

orchestrion, commanded by an Ampico player piano (approx. 1950).

Nancarrows Percussion "Instruments" |

These were the

most interesting to me since I had the experience of watching him make

them. Conlon bought Mexican clay "ollas,"

or pots, of varying sizes; the largest were about 70 cm high and the

smallest about 30cm high. He would take a hacksaw and saw off the bottoms

of these pots about 5cm parallel to the bottom. He would then take kidskin

that he had soaked in water overnight and stretch it over the hole that he

had cut away and tie the skin to a thong he had strapped around the neck

of the pot. This was done in a crisscross pattern so as to get the maximum

tautness on the stretched skin. He would then place this pot upside down,

i.e., skin side up, in the sun until the kidskin dried and shrank very

tightly over the opening he had cut away. Viola! a beautiful drum! And one

that had an unusual and melodic sound.

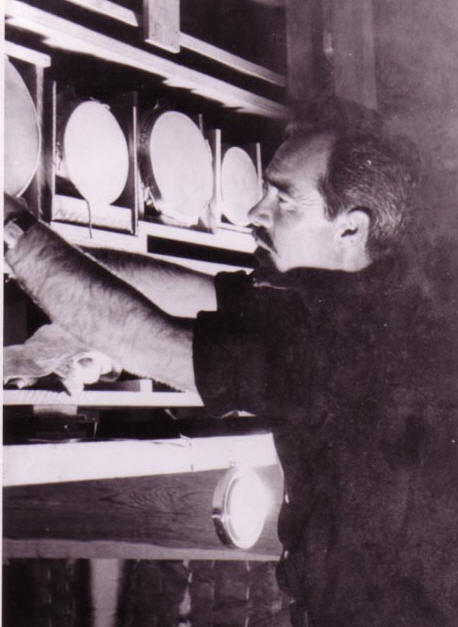

|

|

Percussion instruments Nancarrow built

from Mexican clay "ollas"

or pots. Foto:

J. Hocker

|

These were the

kind of activities that especially delighted me since they were manual and

creative and I, myself, always took delight in working with my hands. When, a couple of years later we were

to move into the Aguilas #48 house, where Conlon had built his studio, he

had a carpenters workbench and all sorts of hand tools there. Tools

fascinated me and Conlon would let me use them, or be with him while he

was working, with no objection whatsoever. He was a perfectly agreeable

and accommodating adult and didn't mind my childhood presence.

As you know

Conlon's drum rack never came to be used as he had envisioned. I think he and Bob eventually gave up

trying to construct the operative mechanism and Conlon finally worked out

his punching machine for his Ampico player pianos. I know he would have

wanted to have at his disposal a greater variety of sounds, but since that

proved complicated, he settled on the piano keyboard as sufficiently

diverse for his purposes. Years later when musicians and composers began

using the synthesizer Conlon remarked to me that, had he been born into

this current generation, he would certainly have composed music for the

synthesizer. Didn't he think he could start now I asked. "No,"

he replied, "it's too late for me now, I already have my niche."

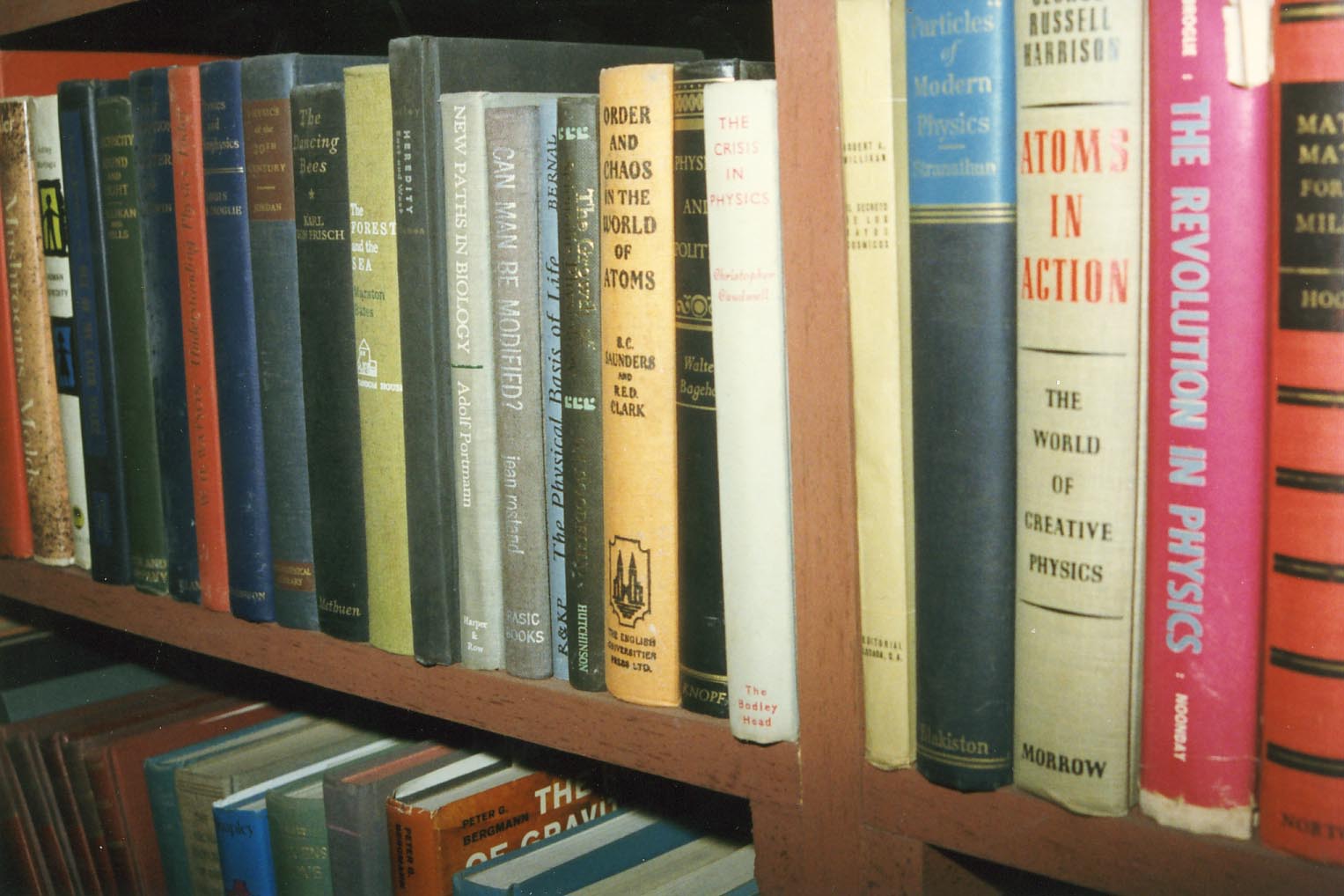

|

Nancarrow owned a huge library. Foto:

J. Hocker

|

Conlon was a

tremendous reader and read books on all the subjects that fascinated him. In addition to books about music he

was also interested in astronomy, language, physics, cooking, mathematical

theory and political philosophy. He read at least three different

newspapers every day. He smoked heavily; three to five packs a day, and

drank small cups of thick, black Turkish coffee, which he would make

himself. He had a whole system of whipping up the fine grounds in a little

copper, crucible like pot to produce a frothy, foamy expresso result. Conlon might have smoked "Gauloises"

occasionally, when he could get them, but his favorite cigarettes for

years were "Soberbios." These were either Mexican or Cuban and

were made with a very strong, dark tobacco, unfiltered, of course.

Conlon never

worked at a regular job. When

I became old enough to ask about this my mother explained to me that he

had received an inheritance from a life insurance policy of his father's

that allowed him to have some sort of steady income.

Conlon gave me

my first introduction to things like atoms and explained what they were. He also told me about the solar

system, stars, galaxies and the universe. These were subjects that I found

very much to my interest and I continue to be interested in cosmology to

this day. He also played chess quite well and we often paired off. Though

he was usually the winner, he would compliment me on my "good game."

One day my mother bought us a children's book on Mozart. This book showed

how Mozart was playing advanced musical compositions on the piano when he

was only four years old. I asked Conlon if Mozart was his favorite

composer. Mozart was one of his favorites, he said, but his very favorite

was Bach. Did Bach ever write any bad music, I inquired. Conlon replied

that as far as he was concerned Bach never composed a single piece of

inferior music. His favorite contemporary composer was Stravinsky. At a

young age I became familiarized with these names.

|

Annettes sons Charles (left) and Luis |

I mentioned

that he was permissive. I

started smoking cigarettes, secretly of course, when I was quite young. Many

of our lunches in the San Angel house we had outdoors in the garden at our

table for four. Invariably,

after lunch Conlon would pull out his pack of cigarettes for a smoke. He

would tap the pack and first offer one to my mother. One day at lunch he

did this. I had my pack hidden in my pocket. He reached across the table

to my mother with his opened pack and said, "dear?" "Oh,

thank you," she said, and took a cigarette. Conlon lit their

cigarettes. I then took my pack out and tapped a few out and reached

across to my brother Charles and said, "dear?" "Oh, thank

you," Charles responded and took one, which I then lit. Conlon

couldn't stop laughing! My mother, also, but she protested. Conlon said to

her, "Don't be silly, let them smoke, what difference does it make!"

I was seven, Charles was eight.

For the

greater part of their marriage together Conlon and my mother lived in

Aguilas #48, where Conlon had his studio at the rear of the property. My mother loved entertaining but, for Conlon, groups of more

than six or seven people were uncomfortable for him. As long as the groups

were small he would be cordial and affable and talkative. But with larger

groups he could get painfully shy and timid and self-conscious. Whenever

my mother had a large party he would invariably run off to his studio and

lock himself away until the people had left. Some of my mother's friends

thought this behavior was antisocial and in poor taste. But most of the

good friends simply explained that this was the way Conlon was.

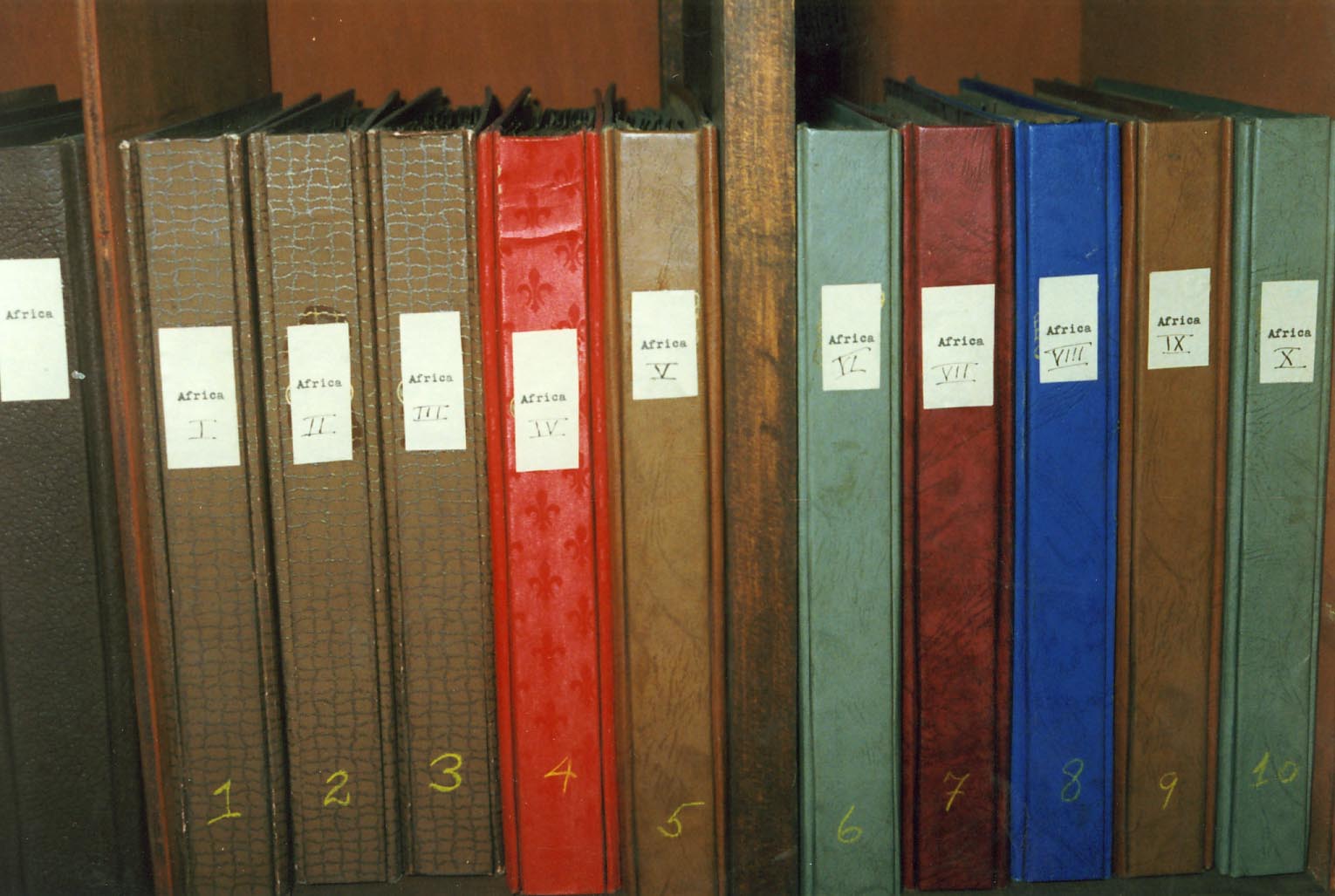

Conlon

collected all kinds of recordings from all over the world. During those years these were of the

breakable, 78rpm variety. He had established a contact in Africa, I'm sure,

but perhaps also in other countries, India or China or the Middle East,

who would mail him records. We used to listen to these in our living room.

So at the age of 10 or so, I was exposed to ethnic music from strange and

distant places and I became accustomed to hearing these sounds; a lot of

chanting kind of music, a lot of drumming.

|

Nancarrow collected ethnic music Foto:

J. Hocker |

At the same time we would often

take invited guests to his studio to listen to his own recent compositions.

With a rather deadpan expression he would play us his latest rolls and

then ask us if we liked this one or that one better. You can imagine how

avant-garde this music sounded in the 40's and 50's! But I grew to like

his music. There was one piece that sounded like bullfight music, like a

piece commonly played during the "fiesta brava" called "La

Virgen de la Macarena." Other pieces were also favorites of mine,

especially those that had a boogey-woogey beat. Years later, when I was in

my late 20's, I would frequently take a girlfriend to his studio to meet

him. We would talk and then have him play his music for us and serve us a

little coffee and odd cookies. His little house and kitchen was an

attractive and artistic den, the music was outlandish; it all made for an

eccentric, wonderful evening.

But perhaps

the best part of his record collection was the jazz. Especially Louis Armstrong! This seemed to be his favorite

interpreter and he would frequently play us many of Louie's recordings. He

loved them and his enthusiasm for Armstrong was contagious so we learned

to love them too. Armstrong would not only play his trumpet and sing with

that unique, raspy voice of his, but he would also talk and joke which

made Conlon laugh with uproarious delight! I remember one particular

record that was in the collection called, "Laughing Louie." This

was an especially amusing piece because it must have been recorded when

Armstrong was high on liquor, and he was laughing and joking and singing

all at once in the most hilarious way. We would ask Conlon to play this

piece again and again and we would laugh throughout the hearing. I wonder

where these 78's are now? I hope Yoko or Mako have retained this

collection.

Conlon had

somewhat of a macabre sense of humor. He, therefore, very much enjoyed the

cartoonist Charles Adams. After

Adams became well known, his cartoons were published in book form. My

mother, or my sister, I don't quite remember whom, gave Conlon one of

these books as a present. As he opened it and read it we would sit beside

him on the couch, because, with his reading of each cartoon, he would

laugh so heartily, and with such amazed surprise, that it became our

pleasure to enjoy his! Conlon always enjoyed a good joke, or dirty story,

and would laugh easily, and this was an endearing characteristic he had.

There was one exception to this. He did not tolerate, nor would he laugh

at jokes that had ethnic slurs. Almost without exception these were met by

stone-faced disapproval and no laughter at all.

Conlon loved

food and would try anything, virtually anything that was edible. He also liked to prepare food, as did

my mother. They were both good cooks and would experiment with new tastes.

As you know Mexicans eat every part of the animal including organs, skin,

viscera, feet, ear, snout, etc. We frequently ate heart, liver, tongue or

brains at our meals as well as more conventional fare. Concerning this

subject there are two things that stand out in my young memory. One is

that Conlon liked smelly cheeses. He would buy some sort of stinky cheese,

then wrap it in what looked like old, dirty, damp rags and hide this

bundle in a dark corner of the closet pantry in our kitchen for several

days. When he would pull this bundle out and unwrap it, the cheese seemed

to be covered with mold, which he would then scrape away to find a gooey,

runny substance underneath. This he would spread on black bread or

crackers and then eat with great delight. The smell used to make me ill; I

could barely control my desire to wretch. Conlon would smile and eat away.

The other memory is of eating "percebes." These are barnacles of

some kind that have a shell-like head and a snake-like body covered with a

cloth-like skin. They are about 6 inches long and are eaten cold and raw.

Conlon would

break the head off and peel the skin back and then eat the reddish brown,

worm-like body that remained. The

more repulsive this looked to me the more he would smack his lips and

exclaim how good it tasted. He was not fazed by the look or bizarreness of

food. For him food was just food and had no psychological connotation. (You

probably have knowledge of the fact that during his time in the Spanish

Civil war, on the battlefield, one of his friends woke up early one

morning only to see Conlon crawling around on his hands and knees eating

grubs and snails that he dug out of the dirt. This is a well-repeated

story.) But Conlon also enjoyed very conventional foods and I remember how

much he loved a rich, chocolate ice cream Sunday, or fresh fruit. He would

pick out and save the best mangos or papayas or pears and eat these with

equal pleasure. He never grew fat and did not watch his diet from that

point of view. One of his great delights was to pick ripe figs from our

garden fig tree, slice them up into a bowl, douse them with heavy sweet

cream, spread sugar on them and have them for dessert.

My brother and

I frequently traveled with my mother and Conlon to Acapulco. But later in their marriage when my

sister Cherry, or other friends of my mother's would join us during the

summer, I think Conlon chose to stay in the city. Conlon liked the beach,

liked to swim as I remember, or read under a thatch umbrella. We usually

stayed at Hotel Mirador, which had cottages high along beautiful seaside

cliffs; this was above the "quebrada" where the divers would

perform their famous swan dives from about 42 meters up. The cottages usually had a hammock for after lunch relaxation and, as I

recall, Conlon would shower quickly to insure that he got to the hammock

before my brother and I did. These were little friendly competitions.

In Acapulco

I would not be

giving you a complete picture of Conlon if I didn't mention his commitment,

especially during the 40's and 50's, to communism. Conlon's politics were always leftist but during the early

years he actually declared himself a communist. My brother and I would

have discussions with him about this and, as small boys we were unable to

articulate a counter position. During college my brother majored in history and

became particularly interested in political theory, and also became

convinced that Soviet communism was as extreme and deplorable as fascism,

though on the opposite pole. So after graduating from the University of

Wisconsin Charles decided it was time to have another discussion with

Conlon about this subject. He had me join him and we both went

over to Conlon's house to talk communism. It was one of those occasions

where the children face their parent, in this case ex stepparent, with a

subject that was always an issue, but where the parent had always been

dominant. My

brother argued persuasively -- by this time he had acquired much more

knowledge on the subject. Conlon was almost unable to defend his position.

It was as if Conlon's political house

of cards just crumbled away. I realized as time went by that Conlon was

not really a political activist of any sort. Other than his experiences as

a young man with the Lincoln Brigade in Spain, which you probably have

much more information about than I have, Conlon was really a non-violent

person who hated racial intolerance. His commitment to communism was a

romantic desire to find a system that would provide social justice among

men, but which he later realized was not the case. In his own words he

says that he became "disillusioned" with communism. I suspect

that my brother Charles still has issues about this subject vis-à-vis

Conlon. You may wish to get his version on this.

After my

mother and Conlon divorced and until he married Yoko, Conlon continued to

live in Aguilas #46. At that

time his compound was only a small bedroom and kitchen attached to his

library and soundproof studio. Neither I nor my mother, nor any of his

friends that stayed in Mexico lost contact with him. We remained on good

terms and visited him with some regularity. He always received us well. He

lived pretty much as a hermit, writing his music, drinking quite a lot,

smoking, cooking his own meals. During

these years I don't know what his love life was like. […] In general, I

considered Conlon my friend, and as mentioned, would visit him either

alone or with a girlfriend, and these visits were always pleasurable. I should mention that since 1964, we

were next-door neighbors.

After he

married Yoko and Mako David was born Conlon's life changed. I can only think that this was a very

positive thing for him. I'm certain he adored Yoko and was enthralled that

he had a son. Mako was about three years older than my oldest daughter,

Phoebe, and four years older than my son, Luis Jose. They would often play

together in our garden.

Stone mosaics by Juan O'Gorman on Nancarrows new house. Fotos:

J. Hocker

With his

marriage Conlon expanded his house. The person involved with this new building project was his long-time close

friend, artist and architect,

Juan O'Gorman. O'Gorman built Conlon and

Yoko a nice two story house and covered many of the exterior walls with

his famous colored stone mosaic

Conlon and O'Gorman shared a healthy

leftist political viewpoint. They also shared ideas about suicide. I

believe it was O'Gorman who introduced Conlon to a book called "Exit,"

that had been published in England, I think. It was a kind of "how-to"

book for taking ones own life. Toward the end of his life O'Gorman talked

frequently to Conlon about this subject to the point where Conlon became

concerned, a concern he shared with me. You may know that some years later O'Gorman did

take his own life in his house in San Angel. To insure that this act would not fail

O'Gorman put a ladder against a tree, tied a sturdy electrical cord around

the tree and then around his neck, then drank cyanide and shot himself

through the temple.

After my third

child, Dustin, was born, my wife and I separated. I moved into a small studio around the corner on Leones

street. About a year later I met Karen and invited her to come to Mexico.

Just at that time, and completely by coincidence, I received a phone call

from, of all people, Helen O'Gorman. She was wondering if I might be

interested in buying Juan's pre-Columbian collection. When I visited her

she also explained her house was for sale, the same house where Juan had

ended his life. This

house was one of Juan's early functionalist structures one block away from,

and in the same style as, Diego's [Rivera] and Frieda's [Kahlo] studio,

which he had also built. The

O' Gorman house included his painting studio. I should tell you that in

addition to being a businessman, I am an artist; indeed this is my real

love, my preferred vocation. I ended up buying this house. Helen

included the collection with the purchase.

Karen and I

began living together here in about 1983. In 1985 she and I were married; our daughter Caitlin was

born in 1986, and our son Tommy was born in 1989. In 1991 we sold this

house and moved back to Aguilas 48, in an exchange where my ex-wife moved

into another residence nearby.

One final

anecdote. Little by little Conlon's music was

becoming more widely known. That is, it was always known in some limited

circles, especially after Columbia, or Decca, I don't remember which

[Columbia], produced his first recordings. But in the late 80's Conlon's music was getting more

notoriety. He had several friends in San Francisco who were backing him. One

was Charles Amirkhanian and another was a woman, Eva Soltes. Conlon confided to me that he was

beginning to get too much mail and that it was hard for him to handle all

this correspondence as well as a demand for his presence at concerts. After several

conversations like this I asked him if he trusted Eva Soltes. To this he replied that he trusted her

fully. So I suggested he consider making her his agent. This he did and

then she began answering his mail and scheduling appearances. Later he

said to me with some pride, "you know I have an agent." I

reminded him that I was the person who had suggested this to him. He

seemed to have forgotten this but then nodded his recollection. Though I

know that he and Eva eventually broke company, I believe that she and

Charles and perhaps others were instrumental in helping him get the

McArthur Genius Fellowship. This was clearly the professional highlight of

his life. Karen and I felt it couldn' t have happened to a nicer person.

Conlon, for years and years had been composing his music, totally

dedicated to this creative enterprise, with no widespread recognition, and

then finally in his winter years and when finances were almost depleted,

he became front-page news in the music world and received a three hundred

thousand dollar prize! What a nice conclusion.

I hope that

what I have written is of some interest to you. I'm sorry that Yoko did not give you my address sooner but

perhaps some of this information could still be pertinent for your

purposes.

My best wishes to you and your family as well for Christmas,

and the best of success for you and your book in the New Year.

Muchos saludos, Luis Stephens

To top

|